One of the key economic indicators we use on this platform is the rate of joblessness. This is the percent of all working age adults (ages 18-64) who do not have a job — either full-time or part-time.

The wording can be a bit confusing. Sometimes you will see the phrase "employment-to-population ratio." This is the opposite of joblessness: the share of the working age adults who do have a job. In our platform, we call this the "employment rate." Sometimes people use the word “non-employment” to describe joblessness, so non-employment and joblessness are the same thing. However, unemployment and joblessness are not the same thing.

Joblessness: All working age adults who do not have a job.

Unemployment: Working age adults who are able to work and are actively looking for a job who do not have a job.

Everyone who is unemployed is also jobless, but not everyone who is jobless is also unemployed.

Unemployment doesn’t count people who are unable to work due to disability or not looking for a job because they are at-home parents, but joblessness does. These people are important to count because they can indicate economic strain. If joblessness is high, a small number of incomes must support a large number of people.

On top of that, unemployment does not count “discouraged workers”: people who are physically able to work, and would like to work, but have given up trying to find a job because they believe none are available. The decision to stop looking for a job says a lot about economic conditions — especially when considering the role of place. If people have given up trying to find a job instead of moving to a place where more jobs are available, then moving must be difficult. It could be the monetary cost of moving or a connection to people where they live, but in any case people who are stuck in places without jobs can get caught in a vicious cycle. Without jobs, people don’t have money to demand local goods or services or invest in local businesses, which leads to fewer jobs, and so on. So it’s important to count discouraged workers, which joblessness does, but unemployment does not.

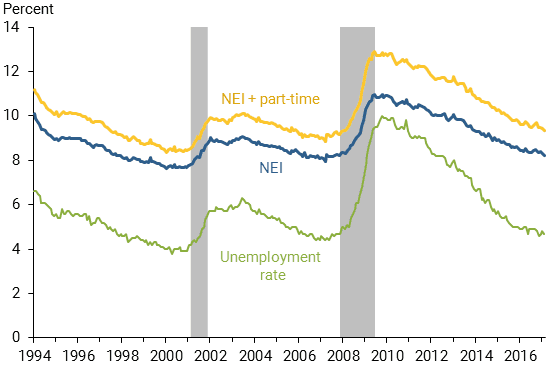

Of course, joblessness and unemployment are highly related. The graph below from the Federal Reserve shows both joblessness (which they call “non-employment” and measure with a Non-Employment Index or NEI) and unemployment at the national level. There are a couple things to notice. First, joblessness is always higher than unemployment because everyone who is unemployed is also jobless, but not the other way around. Second, joblessness and unemployment generally go up and down at the same time because they’re both affected by the availability of jobs, but they don’t move in perfect sync because the amount of people who have stopped looking for a job changes over time.

Unemployment and joblessness/non-employment over time. “NEI” stands for “Non-Employment Index.” Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Unemployment and joblessness/non-employment over time. “NEI” stands for “Non-Employment Index.” Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Joblessness and unemployment are similar ways of looking at the job market and the economy as a whole, but we believe that joblessness contains important information that unemployment could miss. If you’d like to dig into the data on joblessness, you can learn more in this post.